Blessed by Name:

Research of the Beattie Name Origin

Early in the 1900’s, a man named John D. Beatty did an amazing amount of searching out all the early records with the border area of Scotland and England. His paper titled, “In Search of ‘Adam:’ Beatty Families in Scotland and Northern England Before 1600”[1] looks at the different areas where the Beattie name could be found in earliest records. Within this paper he states, because the earliest form of the name was Bettison/Batisoun, “Cleary the name evolved as a patronym of Baty/Betti, but when and how precisely it emerged remains unclear.”

So the question of who Baty/Betti is needs to be addressed. There are over 22 different spelling of the surname. Today in Scotland the common spelling is Beattie, Beatty or Beaty in Ireland and in Northern England is Batie. With the two main pronunciations are ‘BeeTee’ as is said in Scotland or ‘BayTee’ in Ireland and England.

Known Variations of Spelling:

Betti, Bette, Bettison, Betteson, Bettisoun, Batesons, Batysons, Beattison, Beattie, Baity, Battison/ Batison/ Batisoun, Betysoun, Beatty. Beaty, Beatye, Baty/ Batys, Batie/ Baties, Battye, Batye, Bayte, Batteye, Bede, Beede, Beddie

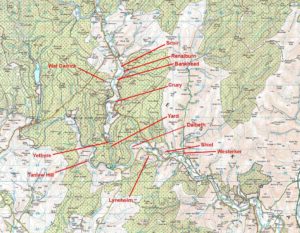

Places that are known Beattie/Batie. . . homesteads are:

Bankhead, Berwick, Corse, Crury, Dalbeth, Davington, Lowther in Dumfries, Lyneholm, Montrose in Forefarshire, Renalburn, Scoir, Shiel, Tanlaw Hill, Wat Carrick, Westerker, Whysgill, Yard, and Yetbyre.

Castle O'er is in this same region of the Eskedalemuir Valley but was a Roman hill fort and not necessarily associated with us. (If you right click the map on the left and download it you may be able to read it better when you save it.)

The Great Vowel Shift

The effects on spelling over time by the Great Vowel Shift[2] cannot be over stated. This vowel shift took well over a hundred years to take full effect and can be heard in what we in modern days call ‘pirate English’ the old or auld way of saying Aye, became Arrh, then on to Yeah today. For places that were battling the English invasion routinely, like the Border region, it took much longer for this conformed way of switching vowel sounds to catch on. In the Borders you can still hear to auld way spoken. If you go to the Borders today and say the name pronounced ‘Bay-Tee’ (Beattie), they have no idea what you mean. You have to say the name ‘Bee-Tee’ (Beattie) and they know exactly the name you mean.

Since our ancestors were more than likely illiterate then much more emphasis on how a name the pronounced had everything to do with how it was written. ‘T’s can sound like ‘D’s and two T’s can be dropped to one and still sound the same. In fact George F. Black states under the entry for the surname Beddie that, “it is probably a form of Beattie. In the northeast, in West Angus, and in East Perthshire intervocalic tt has become dd.” ‘E’s, ‘Y’s and ‘I’s can be interchangeable at times. Emphasis on ‘Bet-tee’ vs ‘Bee-Tee’ or even ‘Bee Dee’ can sound similar. Add to the fact that the writer was guessing on how to spell what they are hearing and the mixture of ways to spell a name can become very varied. I remember back in my high school days in English class and the teacher had just come back from a summer trip to England and he was teaching us about the Venerable Bede, the author of “The Ecclesiastical History of the English People[3]” He wrote ‘Bede’ on the blackboard and I thought, “Looks like that could be said as ‘Bee-Dee’.” That was actually when I started wondering about the origins of the name. I think it is fitting that my research connected to that first point as I remember it so well.

Now if you look at the history given by the lineage site or what I refer to as “canned history[4]” writings on the surname, you will see a reference to a Gaelic word for “food server or vittler” is ‘Biadhtach.’ The Irish chieftains appointed ‘Biadhtachs’ to supply food and lodgings to travelers and clan soldiers when passing through their territories. Because of the silent Irish and Gaelic "dh" and "ch" sounds the sound to ‘Bee Tee.’ In return for providing this service, the ‘Biadhtachs’ were granted lands by the Chieftain and held lordship over seven boroughs. In effect, the ‘Biadhtach’ was the official in charge of public hospitality. But trouble with this being the origin is the word is an Irish Gaelic word and is not found, as such, in Scottish Gaelic. There may very well be a group of people whose name variation did originate from Ireland because the DNA study within the Beatty Project suggests a few family groups that are not related and that may be the origins for them. A case in point for a John Battye I knew growing up, whose family came for Ireland and he pronounced his name ‘Bay-Tee’.

Many of the Beattie’s, especially the Border Reiver Beattie’s, did not make it over to Ireland until King James VI/I united the kingdoms of England and Scotland in 1603, upon the death of Queen Elizabeth I. The surname was already in use before then so that hypothesis does not make sense. In his book “The Surnames of Scotland; Their Origins, Meanings and History,[5]” George F. Black states, “There is no evidence to support the theory that this name is from the Gael word biadhtach, one who held land on condition of supplying food (biad) to those billeted on him by the chief.”

Baties of the Cross or Crose (or Corse) are mentioned by John D. Beatty’s writings also. “Yet another small fortress held in Eskdale was known as the Cross or Corse. Wat or Walter Batie was a resident in the early 1500’s, his son John, called John of the Corse, pledged his support to the Lord Regent in 1569. This was perhaps the same John Batie of the Cross who in 1586 pledged his support of Liddesdale. He was probably closely related to the Baties of Black Esk and those Mungos, who appear on the same list.”

Recorded on a tenants list dated 10 Oct. 1335 is a Nicholas Betteson and the words in Latin, “Constabula Castri de Werksworth od ejus loci tenant,” which translated means, “Constable castle of Werksworth od maintain its place.” Hold on to the name Werksworth, because it will become much more evident that this name is key to who is Betti!

The “family group/grayne” or Clan we are looking at is the one that came from the Eskdale valley and is a descendant of the Border Reivers or Riding Clans. In the DNA study this group is the largest and match much more closely to the other Riding Clans surnames in the Borders such as the Armstrong’s, Elliot’s, Little’s, Bell’s, Thompson’s and Johnstone’s. All of these Riding Clans lived in and around the Eskdale area near Langholm in Liddesdale, Scotland. They were all allies with each other during the medieval time period of the Anglo-Scottish War. The comparisons are seen in the Family Tree Maker DNA Y-chromosome Border Reiver Project which matches the known surnames to each other.

In the Eskedalemuir Valley, just north-west of Langholm, Scotland is a distinct place which was mentioned by Sir Walter Scott in his book, “The Lay of the Last Minstrel,”[6] the passages in Canto 4, X-XII. It reads as follows:

“Scotts of Eskdale, a stalwart band,

Came trooping down the Todshaw-hill;

By the sword they won their land,

And by the sword they hold it still.

Hearken, Ladye, to the tale,

How thy sires won fair Eskdale.

Earl Morton was lord of that valley fair;

The Beattisons were his vassals there.

The Earl was gentle, and mild of mood;

The vassals vere warlike, and fierce, and rude;

High of heart, and haughty of word,

Little they reck'd of a tame liege lord.

The Earl into fair Eskdale came,

Homage and seignory to claim:

Of Gilbert the Galliard a heriot he sought,

Saying, "Give thy best steed, as a vassal ought."

"Dear to me is my bonny white steed,

Oft has he help d me at pinch of need;

Lord and Earl though thou be, I trow

I can rein Bucksfoot better than thou."

Word on word gave fuel to fire,

Till so highly blazed the Beattison's ire,

But that the Earl the flight had ta'en,

The vassals there their lord had slain.

Sore he plied both whip and spur,

As he urged his steed through Eskdale muir;

And it fell down a weary weight,

Just on the threshold of Branksome gate.

XI

The Earl was a wrathful man to see,

Full fain avenged would he be.

In haste to Branksome's Lord he spoke,

Saying--"Take these traitors to thy yoke;

For a cast of hawks, and a purse of gold,

All Eskdale I'll sell thee, to have and hold:

Beshrew thy heart, of the Beattisons' clan

If thou leavest on Eske a landed man;

But spare Woodkerrick's lands alone,

For he lent me his horse to escape upon."

A glad man then was Branksome bold,

Down he flung him the purse of gold;

To Eskdale soon he spurr'd amain,

And with him five hundred riders has ta'en

He left his merrymen in the mist of the hill

And bade them hold them close and still;

And alone he wended to the plain,

To meet with the Galliard and all his train.

To Gilbert the Galliard thus he said

"Know thou me for thy liege-lord and head;

Deal not with me as with Morton tame,

For Scotts play best at the roughest game.

Give me in peace my heriot due,

Thy bonny white steed, or thou shalt rue.

If my horn I three times wind,

Eskdale shall long have the sound in mind."

XII

Loudly the Beattison laugh'd in scorn;

"Little care we for thy winded horn.

Ne'er shall it be the Galliard's lot

To yield his steed to a haughty Scott.

Wend thou to Branksome back on foot

With rusty spur and miry boot."

He blew his bugle so loud and hoarse

That the dun deer started at fair Craikcross;

He blew again so loud and clear,

Through the grey mountain-mist there did lances appear;

And the third blast rang with such a din

That the echoes answer'd from Pentoun-linn

And all his riders came lightly in.

Then had you seen a gallant shock

When saddles were emptied and lances broke!

For each scornful word the Galliard had said

A Beattison on the field was laid.

His own good sword the chieftain drew,

And he bore the Galliard through and through;

Where the Beattisons' blood mix'dwith the rill,

The Galliard's-Haugh men call it still,

The Scotts have scatter'd the Beattison clan

In Eskdale they left but one landed man

The valley of Eske, from the mouth to the source

Was lost and won for that bonny white horse.”

So as the story goes, when King James VI/I united the kingdoms of Scotland and England, he wanted to stop the Border Wars that had been taking place for over 300 years between the two. So he set out to break up the Reivers. The Maxwell’s, Scott’s and the Kerr’s took full advantage of this and started playing nice in order to gain favor of the King by rounding up and handing over the fellow Reivers. In return the King gave lands to these three Clans Chieftains; some would call them traitors, clans. According Sir Walter Scott the King gave the Eskdale valley to Lord Robert Maxwell. As the story goes when he tried to lay claim to the land, he foolishly road in alone and proclaimed to the inhabitants that it was now his land and they must vacate. To which, the Bettison’s were not pleased since they had lived there for many centuries and would not leave it without a fight. Now the chieftain of the Beattison’s was Ronald Beattie and he knew the clan meant to kill Lord Maxwell so he gave Lord Maxwell a white steed to escape on, which he did to the nearest pub! While at the pub he commiserated his circumstances with a group from the Scott’s Clan, he supposedly sold the land to the Scott Clan with the provision that Ronald Beattie be able to hold hereditary title to the homestead of ‘WoodKerrick’ or Wat Carrick as it is now. Needless to say the Scott Clan routed the Beattie’s out of the area and off too many shore’s they did go, mine to Northern Ireland, but others to a young America or Canada.

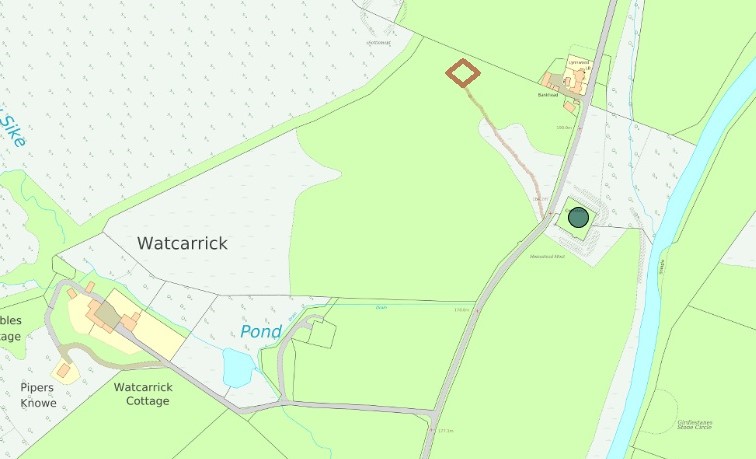

The earliest record of the land known as Wat Carrick, is dated back to 1153 and a Robert Avenel[7] who donated the land to the monks at Melrose Abbey, during the reign of King David I the son of Margaret Aething and Malcolm Canmore. Robert Avenel was a 12th-century Anglo-Norman magnate. He was ruler of the small former Northumbrian province of Eskdale in Dumfriesshire, as well as Abercorn in West Lothian. He was one of a small number of Anglo-Norman immigrants to have been given a provincial lordship in southern Scotland in the early-to-mid 12th century. That the land became associated with the Beattie’s for the next 700 or more years is what links the Beattie’s yet again to the monks. The site Ancient Monuments in the UK[8], states the following about the site, “The monument is the remains of a medieval homestead moat, measuring 29m square within double banks and flat-bottomed medieval ditch. The interior of the enclosure, in which Watcarrick Chapel once stood, is now almost completely occupied by a modern cemetery. It seems likely that the earthwork is a defensive work of the 12th century, predating the granting of the lands of Watcarrick to Melrose Abbey between 1153 and 1165. A U-shaped band 20m broad, extending outwards from the foot of the cemetery wall across the earthwork, is proposed for scheduling. The cemetery and its boundary wall are specifically excluded from the scheduling. The monument is of national importance because it is of a very rare class in the area; few such defensive structures of the period survive. It is therefore worth preserving the little that remains as study of the earthworks will be of national importance to the theme of the history of medieval defensive structures. It is of particular interest because of the relative proximity of the more major medieval earthwork at Bogle Walls.” So an Ecclesiastical History of Chapel in parish of Westerkirk called Watcarrick is mentioned in 1305, and noted as disused by 1722. David I granted lands of Watcarrick and Tomleuchar to Robert Avenal who granted them to Melrose Abbey 1153-65. Watcarrick as a grange of Melrose Abbey mentioned in medieval documents.

John Hyslop writes in his book, “Langholm As It Was” from 1912 says this whole story by Sir Walter Scott was romantic nonsense as he found proof that the property was sold to an Armstrong, except the land known as Wat Carrick today. Evidence has shown also that the original name of the property was Wud Carrick which means basically ‘Wood’ ’Rock,’ which is not hard to see why when standing in that area. A thick forest surrounds the valley and an unusual rock faced ledge can be seen just off to the northwestern edge of the property.

But Ronald Beattie’s family was allowed to stay in the valley for another 250 plus years. The last of Ronald’s Beattie line died in early 1900. William Beattie, the last of Ronald’s descendants killed himself in the barn at Wat Carrick, for the absurd reason that he had contracted ringworm. Not sure that is true but he died in around 1920, so the property has gone out of the Beattie’s possessions. The homestead of Wat Carrick is located approx. one mile south of the Eskedalemuir mountain peak. Within this property is an ancient cemetery known as Wat Carrick Cemetery but the original name was Bankhead Chapel. Archeological references at Canmore.org state that this ancient structure known as Bankhead Chapel is of Anglo-Saxon origin and of indeterminable age.

While visiting this homestead and speaking to the then owner, Mr. Miller, he stated that local legend “has it” that there is a tunnel running from the home known as Wat Carrick to the ‘auld kirkyard’ of Bankhead Chapel. Now standing there in the present day Wat Carrick driveway with my group of Beattie’s, we were very skeptical of this statement but upon viewing the area from a birds view on google earth, it is very easy to see that what is now Wat Carrick was not the original homestead. The original foundation can be seen to be directly across from Bankhead Chapel and up with a ditch running straight down to the cemetery which could be a collapsed tunnel.

The fact that Sir Walter Scott refers to the Beattie’s as Beattison’s and gives us a location that points to an ancient Anglo-Saxon chapel foundation tells me that Anglo-Saxon history is that right direction to look to piece together who the ‘Sons of Betti’ are.

Names have meanings and what is the meaning of Betti or Beati?

The word ‘Beati’ in Latin means ‘Blessed,’ as in the Beatitudes or Blessed-Attitudes and is referenced as such by the translators of the King James Bible in the Beatitudes, (the same King James who disbanded us, by the way.) Latin is the language of the early monks of Lindesfarne’s Holy Island. The Anglo-Saxon/Welsh word for Abbey is ‘Abaty.’ The Old English word for priest is ‘Bede,’ so the Venerable Bede ‘was really the ‘venerated priest.’ All of these words point to an ecclesiastical origin of the name Beattie or Beattison as Sir Walter Scott referred to it.

In around the year 653, four monks left Lindesfarne Island to set out as missionaries to the Anglo-Saxons and Jutes. They were Adda, Betti, Cedd, and Diuma. Betti was of the Benedictine order and believed to be a Saxon by birth, who founded a Christian church in Wirksworth, England and is said to be entombed under the ‘Wirksworth Stone’ there. The Venerable Bede wrote that Peada, who was the son of the pagan king Penda of Mercia, wanted to marry Alchfled, daughter of the Christian king Oswiu of Northumbria. Oswui agreed on the condition that he became a Christian. On hearing the Gospel, he willingly converted. Bede says that Peada was baptized at a village called At-Wall, which may be Walton near Newcastle. Alchfled came south with these four priests in 653. In 1820 a Saxon grave-lid was discovered in the chancel of the church. Known as the ‘Wirksworth Stone’ and highly decorated with religious scenes, it is dated to before 692A.D. Beneath this stone lay a well preserved skeleton of a tall man, probably that of Betti. Here is a quote from Venerable Bede’s writings, “He was chiefly induced to receive Christ’s faith by a son of king Oswio, named Alhfrith, his kinsman and friend, who had married his sister, Cyneburg by name, daughter of king Penda. Then he with all his companions, who had come with him, and the king’s followers and all their servants, were baptized by bishop Finan at the well-known town of the king which is called Walbottle. And he received, and the king made over to him, four priests to baptize and teach his people, who were by their learning and their life men of power and virtue; and he returned home full of joy. The priests were thus named, Cedd, Adda, Betti, Deoma.”

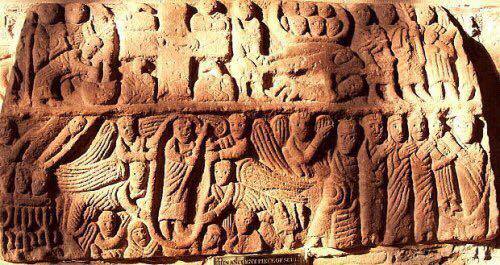

The exact date of Betti’s death was not recorded but it is eminently possible that he was buried beneath the Wirksworth Stone. The upper register of the carvings includes a crucified lamb, which of course represents Jesus, ‘the Lamb of God who takes away the sins of the world.’ Christian Iconography has always had the purpose of communicating the truth of the Gospel, but in the seventh century, people were not as literate as they are today, and some Christians leaders were worried that a representation of a crucified lamb might mislead some people into thinking that it really was a lamb, rather than the man Jesus who was crucified. This was one of the matters discussed at a Christian Council held in Constantinople in 692. They issued a canon or church law that banned such artistic depictions of Jesus Christ, so the stone must have been carved either before 693 or else defied the canon law which seems much less likely. Everything about this artifact is consistent with it having been the cover of Betti’s grave, which is an exciting confirmation that Bede and others who documented Anglo-Saxon history were recording real facts, real events and the activities of real people.

(The burial stone over the Benedictine Monk Betti in Wirkswork England)

(The burial stone over the Benedictine Monk Betti in Wirkswork England)

Since the monk Betti was well known to the Anglo-Saxon’s then it is not inconceivable that Margaret Aetheling, herself a devout Benedictine, would have made a pilgrimage to Wirksworth England to see the ‘Wirksworth Stone.’ As stated Edward A. Freemans book, “The History of the Norman Conquest of England, It’s Causes And it’s Results,[10]” Margaret Aetheling was born in Hungry as the oldest granddaughter of the king of England at the time, Edmund Ironsides, her father, Edward, being next in line to the throne. They returned to England in 1057 but her father Edward after returning, died on 5 Jan. 1066 and William, the Duke of Normandy, took full advantage on 28 Sept., 1066 landing on the southern shores of England. By the 25th of Dec. William was crowned king. Rebellions against William sporadically spring up over the next two or more years. But Margaret had ample time to visit the Wirksworth Stone in St. Mary’s Chapel between 1057 and 1066.

Soon after William came to England, he issued the edict of the use of surnames to help the new ruler differentiate the people of the region better. Margaret left England intending to return to Hungry in 1069 but was blown off course and back to the shores of Scotland. Malcolm Canmore or Malcolm III was the King of Scotland at this time, having killed MacBeth to take the throne to avenge his father death. Malcolm fell very much in love with Margaret and married her in 1070 in Dunfermline Abbey, producing several lines of good kings for Scotland. King William was not pleased by the union, thinking it could lead to Scotland gaining power to overtake his conquest. William started persecuting the churches with in England. Margaret sent Malcolm down to Wirksworth to bring the churchmen to safety in Scotland. I believe Malcolm brought the ‘sons of Betti,’ or followers of the Wirksworth monastical leadings of the monk Betti, up to Scotland.

As to whether or not Betti had sons, I do not know, but monks were not celibate at this time period. These ‘Sons of Betti’ could be either actual descendants of the monk Betti or followers who took on the name of their association to the order he founded in the Wirksworth area. Having a wide variety of followers DNA would add to some of the variations now seen in the DNA within the Beatty Project DNA data. The skeleton found under the ‘Wirksworth Stone[8]’ was a male over 6 foot tall which would have been a commanding presents in the seventh century. Not much else is known about the man Betti but it has been long held that he came from a wealthy family that converted to Christianity and sent him out to Lindesfarne’s Holy Island to be educated.

Queen Margaret’s biographer and the monk confessor, Turgot[9], wrote that Margaret would be continually paying ‘blackmail’ money to free Englishmen who were being held for ransom. The term ‘blackmail’ originates from the Border Reivers. It is also worth noting that many people of the Borders were families that were driven north by the Norman Conquest. In fact very few names had their origins in that region prior to the Norman Conquest. The Beattie’s case is marked by the fact that when studying the monastic settlement map of Scotland, the only places where the Benedictines settled are matching to the earliest records found for the Beatties.

It is also worth noting that within the many settlements that had at one time laid along the Esk Rivers, John D. Beatty’s paper, mentioned above, tells of one settlement that had a distinction of those in it were referred to as ‘Mungo’s.’ The term ‘Mungo’ is a Gaelic word for ‘Beloved,’ and is associated with a Scottish St. Mungo. Now during the Reiver time, who among the Reivers could possibly be called by such a term? Yet in 1590, John Batye of Warrick was called “Mungo’s Johnne,”and together with Andro Batye called Mungo Hew’s Andro, appear on a list with various Armstrong’s as being ordered to appear before the Warden of the Western March. There are other settlements mentioned in John D. Beatty’s paper up in the area near Aberdeen and those Beatson’s have an extensive genealogical record written by Alexander John Beatson of Rossend, but his coat of arms looks very different from that of the Border Beattie’s. Also the Beatson’s of the Aberdeen area were much more affluent and had greater exploits then the Border Beattie’s. They had amongst them sea captains and Jacobites who fought at the Battle of Cullen Moor. They may even hail back to the legendary Beatons physicians of the Middle Ages in the Highlands but I tend to doubt that due to the fact that those Beatons were under Clan MacBeth and had been in Scotland a long before the Norman Conquest.

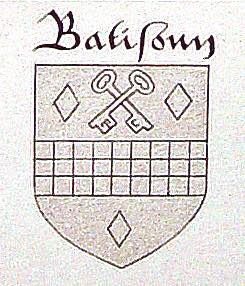

(The ancient coat of arms for the Batison’s, a page from Robert Bruce Armstrong's classic,"History of Liddesdale, and the Debateable Lands," showing the major ‘Reiving’ Surnames of the area)

(The ancient coat of arms for the Batison’s, a page from Robert Bruce Armstrong's classic,"History of Liddesdale, and the Debateable Lands," showing the major ‘Reiving’ Surnames of the area)

Coat of Arms / Shield / Motto

As to the Beattie Coat of Arms, author John Hyslop wrote in “Langholm As It Was,[12]” that some of the gravestones in Westerkirk, Canonby, and Ewes churchyards, and also in that of Carruthers, bear the arms of the Beattison Clan, and these sculptured arms are similar to those of the different families of Beattie, or its synonyms, found in most of the churchyards of the Borders. In virtually all of the arms, the cross-keys and the “draught-board” design are found but it does not necessarily follow that both or either of these indicates an armorial bearing. The Cross-keys are found in many ecclesiastical coats, and are the emblems of St. Peter. In medieval times they were a common sign of inns attached to religious houses.

More modern versions of the coat of arms has been revised with two keys but not crossing. I believe this is because our clan or family/grayne has drifted from our ecclesiastical roots and the newer versions depict that. Here is some of what John D. Beatty wrote about the coat of arms, “One should not attach too much importance to the fact that the design (below) was not formally registered with the Lord Lyon. These were a warlike people living on what was then frontier, and it is not surprising that the design was not registered. It is also probable that heraldic rules about the bearing of arms were not followed, and more than one person used a device of identical design, even though they were on distantly related.”

Meaning of the symbols of the Beattie ‘Coat of Arms,’ red represents military strength and glory, silver and white represent peace and sincerity and blue represents loyalty and truth. Crescents represent someone who has been honored by the King. The open-bar style, forward-facing helmet indicates the highest ranks of nobility. The Motto, 'Lumen Coeleste Sequamur' means, ‘Let Us Follow the Light of Heaven’ or ‘May we follow heavenly inspiration.’ The pointed line is a Chevron, which represents the roof of a house. It indicated the rank of the bearer of the coat of arms.

Other versions of the coat of arms have keys, which represent knowledge, guardianship, and dominion, diamonds or lozenges, which represent noble birth, persuasion, honesty and constancy and a sword, which represents military honor and should incite the bearer to a just and generous pursuit of honor and virtue in warlike deeds. It is also symbolic of liberty and strength. In the middle ages, the sword was often used as a symbol of the word of God. The sword (especially borne with flames) is also a symbol of purification. Add an interpretation of the coat of arms to the right by Clifford Johnston, a genealogical heraldrist, says "the 3 roundels or spurs indicates a 3rd son. The roundels are star-shaped and in the shape that was used by the Kights Templar. The crescent indicates a connection to the Holy Land - Crusader probably and or a KT connection again."

The sword of the word of God and the motto of ‘let us follow the light of heaven’ again points to an ecclesiastical origin of the Beattie surname. The motto obviously came about well after the time of monk Betti but speaks of a heartfelt conversion to the Lord Jesus Christ. For Christ is the Light of the world.

The Beatson motto is ‘Cum prudentia sedulus’ which means ‘Diligent with prudence.’ An interesting note is the motto for the Battye surname is ‘Ducat amor Dei’ or ‘Let the love of God lead us,’ now that doesn’t sound like the motto of a vittler.

The “Book-a-Bosom Priest”

The Anglo-Scottish Borderlands were often laid waste in the times of the Border Reivers or raiders. The Church, reliant for its temporal welfare on the produce of its parishioners, suffered greatly. As the Border Reiver raids on each side of the English Scottish Border became a way of life, lands and crops were burned and cattle, sheep and insight or household goods were stolen. This led to a society on two levels. There were those who were strong in arms and numbers who reived on a regular basis and defied any to take back what was stolen. Others of a weaker and more pacific nature were left destitute and hungry; victims of the relentless crime. They had nothing to give to the Church.

In a society where care for the soul and a happy afterlife still dominated the lives of many, the mainstay of the community was the Church. It relied for its temporal needs on a portion of the produce of the people who worked, often toiled in the fields, and a percentage of the meat which they nurtured and fattened. Should the community, be it steading or village, suffer at the hands of an opportunistic Border Reiver, and lose cattle, sheep and crop, then the Church takings would be mean indeed. “Churches are abandoned throughout the English Scottish Border Lands"

In a very short time the community was unable to support the Church and many of the priests were forced to leave and try their luck elsewhere. Churches in the Border country were abandoned for many a year, others dismantled by a people who saw no future use for the House of God. Moreover the Borders became a no-man's land for the better of the church fraternity; many were scared to minister in such a violent society with the result that un-ordained 'priests' entered the country and did little to administer to the spiritual needs of the community.

The parish of Ettleton in Liddesdale was without a minister in the years 1576 through to 1589. The parish of Castleton, in the same valley, was vacant during the same years. It was an intolerable situation, rife throughout the Anglo-Scottish Border, and not easily remedied. The nurture of the soul became almost non-existent at a time when the fear of God might have helped to improve the ways of a hard and obdurate people.

In 1525 there was a violent reaction from the Border Reivers after they were cursed by the Archbishop of Glasgow, one Gavin Dunbar. In his famous 'Monition of Cursing', a rant which runs for over fifteen hundred words, he cursed the reiving families and clans: every part of their bodies from head to foot, and prophesied eternal damnation unless they changed their ways. Time would show that it was the wrong approach to a people who had suffered every type of degradation from loss of life to livelihood. The Armstrongs of Whithaugh in Liddesdale were particularly incensed by the Archbishop's meddling and proceeded to knock down churches within their vicinity.

Enter the Borders the Book-a-Bosom priest, an itinerant priest, a wandering priest, who would walk the Borderlands at a time when many were afraid to enter its confines, and preach to the people. Even in the lands of the Border Reiver families with the fiercest reputations he was tolerated, if not welcomed. He wandered from village to village administering his spiritual help and guidance at the Market Cross, the focal point of the community, or any wayside cross-road. He carried the 'Good Book' within his garments, hence his title.

One particular tradition that is still remembered today is that of 'hand-fasting'. Indeed there are still places named ‘hand-fasting haughs’ (or halls) in the Scottish Borders. Should a couple fall in love and wish to be married, then, because there was no priest present in their community, they would promote their relationship by the joining of hands and wait for the day that the Book-a-Bosom returned to their area to cement their union. It could be more than a year before the priest returned. Should the relationship breakdown in the meanwhile then the one who broke it was responsible for any children that followed the 'hand-fasting'. Should the relationship survive then it would be recognized and sanctified by the church by the Book-a-Bosom priest.

In the Eskedalemuir Valley where the White and Black Esk Rivers met is the traditional place where ‘hand-fasting’ ceremonies’ were done. This area was within the middle of the Beattie’s multiple settlements.

Also just north of this place is another religious site called ‘Over Rigg’ which is a ‘natural amphitheater’ along the western side of the White Esk River. Canmore.org.uk[13] Archaeology group has identified this as an ‘Ancient Earthwork’ first excavated in 1900 by R. Bell and described in John Hyslops book, ‘Langholm As It Was.’

About this site Canmore says the following, “This enclosure was presumably originally circular, but has been eroded away by the White Esk, almost to a semicircle, with a chord of 200' and a radius c. 85'. It is surrounded by an inner ditch 3' - 4' deep and 13' wide; a concentric rampart 5' high and 18' broad; and an outer ditch 3' deep and 15' wide, with a slight mound on the counterscarp. Towards the N for c. 60' the outer ditch appears to have been filled up. At a higher elevation, there passes around the enclosure a terrace 10' - 12' broad, changing to a ditch where it makes a return at either side towards the river. (1906 by R. Bell) The interior of the enclosure, which was excavated, is higher than the exterior. He found that the subsoil was blue clay; logs had been laid on it to form a floor; the logs had decayed, but the bark remained. On top of this was paving on which c. 18" of peat had grown. Covering an area 40' in diameter in the center of the enclosure was an 18" thick layer of rough stones, below which was a great quantity of minute fragments of cremated bone, none over 1" long, resting on a layer of charred wood mixed with the clay. The paving, charcoal and burnt bone was noted by the Bell as exposed in the section made by the river erosion.

These enigmatic earthworks are generally as described. The circular work is situated on the flood plain in a natural amphitheatre-like hollow while the outer work lies on the slopes above. Neither appears to have an entrance. While these earthworks are probably prehistoric, their form of construction and situation do not suggest a habitation site. The low-lying situation of the circular enclosure compares with that of the Girdlestanes and the possibility exists that this is a funerary or religious monument. . . This enclosure is situated at the foot of a steep-sided hollow 700m NE of Castle O'er fort now roughly D-shaped on plan, it measures 52m by 20m internally. The chord is formed by the River White Esk and the arc by double ditches and a medial bank. On the NNE and SSW there are short stretches of outworks consisting of a bank and external ditch. There is no sign of an entrance and it is likely that the river has eroded part of the enclosure.

In 1901 Bell reported that trenching within the interior had revealed a layer of logs covered by cobbling; fragments of burnt bone were found. . . (1980 by RJ Mercer) Archaeological excavation was undertaken due to the perceived threat of erosion by the River White Esk. Geomorphological stu dies have suggested that erosion will not be a problem in the future. This led to attempts to determine the rates of change in the fluvial system, and the long-term (the past 2000 years) reconstruction of the behavior of the incised menader at Over Rig. Radiocarbon dating of the most extensive Flandrian river terrace shows it to have formed around 2000 BP, that is the period of initial intensive occupation of the White Esk valley. . .(1989 by R. Tipping) Pollen analyses were undertaken through a 1.50m thick peat sequence growing within the inner ditch of the enclosure. The stratigraphic relationships indicated that this sequence accumulated throughout the historic period. Initially, correlations between the pollen record and the known documentary record for the area immediately around the site were made assuming a linear accumulation rate for peat growth; such correlations, particularly that between a major intensification of pastoralism and the takeover of the valley from an Anglo-Norman lord by Cistercian monks in the eleventh century, seemed particularly convincing. A series of five radiocarbon dates throughout the sequence, assayed by the SURRC laboratory under Dr. G. Cook, suggested that, instead, peat growth was extraordinarily rapid, and limited to a short period during Romano-British times. Several of the dates, however, pre-dated five closely-grouped radiocarbon dates from wood found in the primary infill of the ditch, and so are presumed in error. Additional dates on wood within the peat have not helped the interpretation, and a series of radiocarbon dates is currently in progress to investigate the hypothesis that severe contamination of the peat and wood samples by older carbon has occurred. ” (Underlined emphasis added)

It is evident that religious rights were being performed in this valley for many years at the ‘hand-fasting haugh’ and Over Rigg locations, as well as the remains of the Anglo-Saxon church foundation at the archaeological site known as Bankhead chapel. It is therefore only logical to assume that if the Beattisouns had a connection to the church that they would have settled near or around the places of religious significance to the inhabitance.

***Further research is being done on the possible connection of the Beaton's of the Highlands who were said to be the Physicians to the Laird's and the Beatson of Kinross in the Pictish region near Aberdeen, to determine a very distant connection to the Beattisouns of the Borders. ***

In Conclusion:

The Beattie's of Liddesdale have never been officially recognized as a clan by the Lord Lyons of Scotland. We haven't had a chief since Ronald Beattie gave the white horse to Lord Maxwell in whatever year we were forced out. We are scatted children of the Broken Men of the Debatable Lands. It is my belief that we were either actual son's of the monk Betti or we were fervent converts whose descendants were disciples of the monk for we took his name.

For much more Beattie Family information, please take a look at the lineage collect and data as The Beatty Project 2000 and their corresponding DNA project. The Beatty Project has a wealth of information on all spellings of the surname.

Sources:

[1] John D. Beatty, “In Search of ‘Adam:’ Beatty Families in Scotland and Northern England Before 1600,” reference pages 1, 4, 5, 7,8 & 9.; printed copy on 15 July 2007 from online source at: http://www.electricscotland.com/webclans/atoc/BeatyHistory.pdf

[2] Richard Norquist, “What Was The Great Vowel Shift?”; Article source accessed 1 Aug., 2018 online at: https://www.thoughtco.com/great-vowel-shift-gvs-1690825

[3] The Venerable Bede, “The Ecclesiastical History of the English People” written in the year 735 approx., reference- book 3,section- XV; source accessed 1 Aug., 2018 online at: http://www.yorku.ca/inpar/Bede_Miller.pdf

[4] Forebears is a genealogy portal or online directory website; accessed 8/17/2018 at http://forebears.co.uk/surnames/beattie

[5] George F. Black, “The Surnames of Scotland; Their Origins, Meanings and History,” page 64; reference book printed 1946;Publications Office, The New York Public Library, New York, N.Y.; IBSN- 0-87104-172-3

[6] Sir Walter Scott, “The Lay of the Last Minstrel,” reference Canto 4, X-XII; source accessed on 1 Aug., 2018 online at: http://www.theotherpages.org/poems/minstrel.html

[7] POMS; Paradox of Medieval Scotland 1093-1286; online records of Donation for Tomleuchar and Watcarrick properties to Melrose Abbey; accessed online on 27 August 2018 at; http://poms.cch.kcl.ac.uk/db/record/factoid/49011/

[8] Website; ‘Ancient Monuments of the UK’; accessed online 27 Aug. 2018 at: https://ancientmonuments.uk/121827-watcarrickearthwork-140m-south-of-bankhead-annandale-east-and-eskdale-ward#.W4QS97gnbIV

[9] Turgot, Bishop of St. Andrews, Ecclesiastical Biographer; “The Life of St. Margaret, Queen of Scotland,” source accessed 1 Aug., 2018 online at: http://www.royaldunfermline.com/Resources/life_of_%20st_margaret_turgot.pdf

[10] “Wirksworth Parish Records 1600-1900”, Wirksworth, England; online source accessed 1 Aug., 2018 at: http://www.wirksworth.org.uk/X559.htm

[11] Edward A. Freeman, M.A., Hon. D.C.L., & L.L.D.; “The History of the Norman Conquest of England, It’s Causes And it’s Results,” written in 1867-79; source accessed 1 Aug., 2018 online at: https://archive.org/details/historyofnormanc06freeuoft

[12] John D. Hyslop and Robert Hyslop; “Langholm As It Was” book written 1912; source accessed 1 Aug., 2018, online at: https://archive.org/details/langholmasitwashhysl

[13] Canmore Archaeological Group, R. Bell excavation notes 1906-1989; Canmore ID- 67422; Site Number- NY29SW 8; online accessed 30 Aug.2018 at: https://canmore.org.uk/site/67422/over-rig

This work is credited to Carol Beattie Selbiger, PG

All uses on or after Dec. 19, 2018 are copy right reserved by the author and all uses of this material without the expressed consent of the author, is prohibited.